Deconstructing Chaos

The magical city of Beirut contains many layers within its architectural make-up. Cassidy Hazelbaker explores the city’s fascinating structure and what is being done to restore it after countless years of destruction.

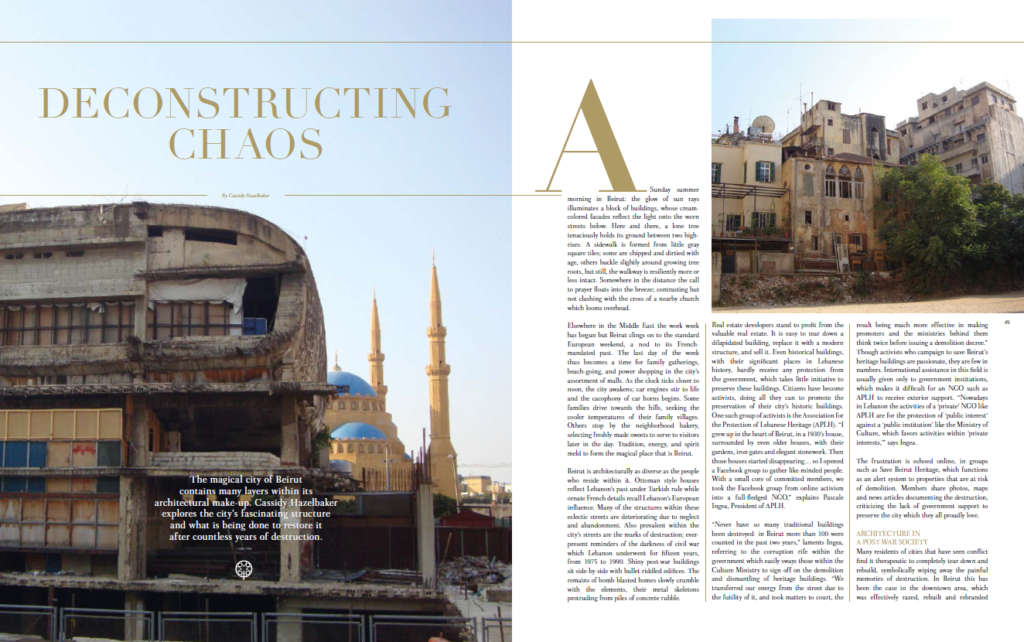

A Sunday summer morning in Beirut: the glow of sun rays illuminates a block of buildings, whose cream-colored facades reflect the light onto the worn streets below. Here and there, a lone tree tenaciously holds its ground between two high-rises. A sidewalk is formed from little gray square tiles; some are chipped and dirtied with age, others buckle slightly around growing tree roots, but still, the walkway is resiliently more or less intact. Somewhere in the distance the call to prayer floats into the breeze; contrasting but not clashing with the cross of a nearby church which looms overhead.

Elsewhere in the Middle East the work week has begun but Beirut clings on to the standard European weekend, a nod to its French-mandated past. The last day of the week thus becomes a time for family gatherings, beach-going, and power shopping in the city’s assortment of malls. As the clock ticks closer to noon, the city awakens; car engines stir to life and the cacophony of car horns begins. Some families drive towards the hills, seeking the cooler temperatures of their family villages. Others stop by the neighborhood bakery, selecting freshly-made sweets to serve to visitors later in the day. Tradition, energy, and spirit meld to form the magical place that is Beirut.

Beirut is architecturally as diverse as the people who reside within it. Ottoman style houses reflect Lebanon’s past under Turkish rule while ornate French details recall Lebanon’s European influence. Many of the structures within these eclectic streets are deteriorating due to neglect and abandonment. Also prevalent within the city’s streets are the marks of destruction; ever-present reminders of the darkness of civil war which Lebanon underwent for fifteen years, from 1975 to 1990. Shiny post-war buildings sit side-by-side with bullet-riddled edifices. The remains of bomb-blasted homes slowly crumble with the elements, their metal skeletons protruding from piles of concrete rubble.

Real estate developers stand to profit from the valuable real estate. It is easy to tear down a dilapidated building, replace it with a modern structure, and sell it. Even historical buildings, with their significant places in Lebanese history, hardly receive any protection from the government, which takes little initiative to preserve these buildings. Citizens have become activists, doing all they can to promote the

preservation of their city’s historic buildings. One such group of activists is the Association for the Protection of Lebanese Heritage (APLH). “I grew up in the heart of Beirut, in a 1930’s house, surrounded by even older houses, with their gardens, iron gates and elegant stonework. Then those houses started disappearing… so I opened a Facebook group to gather like-minded people. With a small core of committed members, we took the Facebook group from online activism into a full-fledged NGO,” explains Pascale Ingea, President of APLH.

“Never have so many traditional buildings been destroyed- in Beirut more than 100 were counted in the past two years,” laments Ingea, referring to the corruption rife within the government which easily sways those within the Culture Ministry to sign off on the demolition and dismantling of heritage buildings. “We transferred our energy from the street due to the futility of it, and took matters to court, the result being much more effective in making promoters and the ministries behind them think twice before issuing a demolition decree.” Though activists who campaign to save Beirut’s heritage buildings are passionate, they are few in numbers. International assistance in this field is usually given only to government institutions, which makes it difficult for an NGO such as APLH to receive exterior support. “Nowadays in Lebanon the activities of a ‘private’ NGO like APLH are for the protection of ‘public interest’ against a ‘public institution’ like the Ministry of Culture, which favors activities within ‘private interests,’” says Ingea.

The frustration is echoed online, in groups such as Save Beirut Heritage, which functions as an alert system to properties that are at risk of demolition. Members share photos, maps and news articles documenting the destruction, criticizing the lack of government support to preserve the city which they all proudly love.

Architecture in a Post-War Society

Many residents of cities that have seen conflict find it therapeutic to completely tear down and rebuild, symbolically wiping away the painful memories of destruction. In Beirut this has been the case in the downtown area, which was effectively razed, rebuilt and rebranded into über-luxurious shopping, dining and office spaces by the development company Solidere. Though many supported the move, others did not. Some critics claim that downtown Beirut has lost its soul and is no longer accessible to the average Beiruti, while others cite that by erasing all vestiges of war, Lebanese are ignoring and glossing over their past without addressing lingering social, religious and political discord.

The demolition of downtown Beirut was a shocking sight to Lebanese architect Mona Hallak, who recalls ”the sight of the Burj Square being flattened by bulldozers was too painful and my first reaction was that we lost our downtown to a real estate company; we have to save the rest of Beirut’s heritage.”

“When history, identity, and collective memory are weighed against money, money wins in a mercantile society with no civic belonging,” says Hallak, musing on both the real estate situation in Beirut and Lebanese society in general. “The Lebanese have not since the end of the civil war engaged in a serious nation-wide attempt at reconciliation. People have not forgiven. People want to avoid remembrance but in effect they are actually falling into the trap of fighting again.”

This desire to preserve Beirut’s historical buildings and to make a statement within Lebanese postwar society led to the establishment of the Beit Beirut (Beirut House) project in 2003, after six years of tireless campaigning for a decree of expropriation for the Barakat building, which Hallak finally received. “The loss of Downtown Beirut to Solidere had its toll on many preservation activists who became convinced that we stand helpless against real estate greed. I personally never was discouraged. To me this fight was one of survival: I want to live in a human city and the heritage clusters in Beirut give me that. I was fighting for the Beirut I wanted my children to grow in, to love and respect,” explains Hallak.

The Beit Beirut project involves the restoration of one of the most damaged buildings along the Green Line, Damascus Street, which used to be a sniper post during the war. The building will be transformed into a cultural center, museum of the city of Beirut, and an urban planning meeting place. Beit Beirut seeks to be a neutral community meeting space that promotes the love of Beirut to all visitors, regardless of which community they belong to or in which area of Beirut they reside. The building’s restoration should provide a place for meeting and reconciliation, a space for memory so as not to be swept up by amnesia. Contrary to what some call a wound still too raw to touch, Hallak says, “I think that human feelings unite, loss unites, pain unites, and people who lost beloved ones find relief in other peoples’ stories about their own loss. I think going down to the essential human experience of a human soul during war will present a memory to share and build upon rather than numbers and dates and names to fight upon. It is time to look at the war as a whole, to try to assimilate it, accept it and forgive, or else we might fall into its trap again.”

Beirut’s Architecture in Contemporary Society

Though appreciation of Beirut’s rapidly disappearing historic buildings is increasing, there remains much work to convince many Lebanese that this architecture is worth saving. In a delicate post-war society that is slowly healing its civil wounds in the midst of regional sectarian conflict, a topic which unites members of different religious and social groups is a valuable tool. “Architecture is a common trait of the people and normally when something threatens this, it is enough reason for the people to stand up to this common threat,” observes Ingea. “The problem is that not all Lebanese feel this is a threat. Many simply welcome this ‘newness’ because they would rather have towers and malls than historical buildings. We differ as Lebanese, by how we view culture, history and tourism. Many of us don’t identify with historical buildings.”

“Usually the younger generation is more enthusiastic about heritage preservation as they feel the need to have a better urban environment and have come to appreciate the qualities of heritage clusters in many areas like Jemmayze and Achrafieh where most heritage buildings have turned their charming ground floors to restaurants and pubs,” adds Hallak. Young Lebanese are highly active on social media, providing a powerful platform to spread the word about Beirut’s rich heritage and beautiful historic buildings that are at risk.

Recently, Minister Selim Warde formed a committee of architects and urban planners to review demolition permit applications and also decline those of unique and important buildings. “The pressure from owners is huge and it is a brave step in the absence of a law for heritage protection,” says Hallak. “The last draft of a law was approved by the government in 2006 and sent to parliament, where it rests in a drawer ever since.”

Citizens should keep Facebook posting, tweeting, and holding candlelight vigils for their treasured heritage. Perhaps with enough pressure, politicians will reopen this drawer to prioritize Beirut’s historical preservation. The fate of Beirut’s older buildings ultimately depends on government legislation. Until then, Beirutis will continue to go about their lives, spending time with family and friends, enjoying their country’s beautiful mountains and beaches and tensely awaiting regional developments. The sun’s rays will still illuminate the Mediterranean skyline of Beirut as the sun rises and sets, as new days begin. Ingea and Hallak, in addition to others, will continue their campaigning for change.